A fundamental religious belief held by the ancient Egyptians was that life on earth was only the first part of their journey in this world. They did not believe in death, per se. Death was considered a transition into the afterlife or another realm of eternal paradise, the Field of Reeds or Field of Offerings, A’aru. This was considered a reflection of one’s life on earth. Essentially, the goal was to make life on earth worth living eternally.

Their perception of death was solely influenced by their firm belief in immortality. To ensure the continuance of life after death, the ancient Egyptians paid homage and made offerings to the gods and deities known as the Seven Hathors.

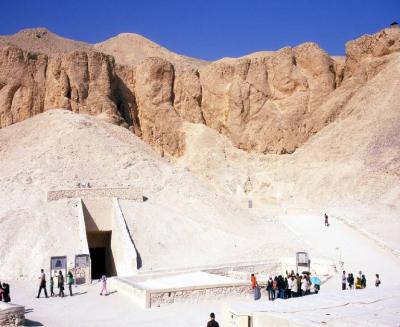

Upon death, the ancient Egyptians believed one had to be mummified in order for his soul to return to the body and continue on the eternal journey to the promised afterworld. Through mummification, the corpse would be transformed into a new body, destined to live and rise again. The preservation of the corpse was vital because the ancient Egyptians believed that the soul and personality of the dead continued to live in the body even after death. Without the body, the soul no longer existed.

Items such as household goods, food, and drinks—on the most basic level, these items are much more abundant and lavish the higher one’s social and economic status is—were placed on offering tables near the tomb. They believed that the person would need these items in the afterworld. Funerary texts, spells, and prayers were also included to help the dead on their journey.

The ritual of preparing the dead for the journey was quite elaborate. It first begins with the opening of the mouth ceremony. This was performed by priests. It involved purification, the burning of incense, holy incantations and lastly touching the mummified body with a variety of ritual objects to restore the five senses. This ceremony was originally only performed on statues of the pharaohs in their temples. However, by the time of the new kingdom, it was more widely performed on mummies.

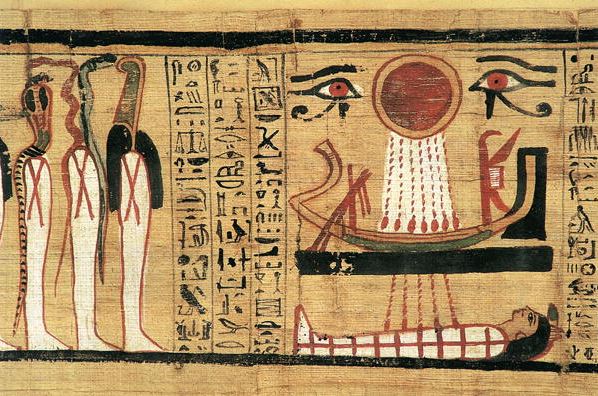

The journey to the afterlife was thought to be arduous, tumultuous, and full of dangers. The deceased traversed the underworld on solar bark first. In the underworld there lived serpents equipped with elongated knives, fire-breathing dragons, and five-headed reptiles. Once the deceased pass through the underworld, they arrive at the Land of the Gods also known as the realm of the Duat. They would then pass through seven gates, reciting a spell at each gate. If they are successful and recite the verses correctly, they will arrive at the Hall of Osiris and prepare for judgment.

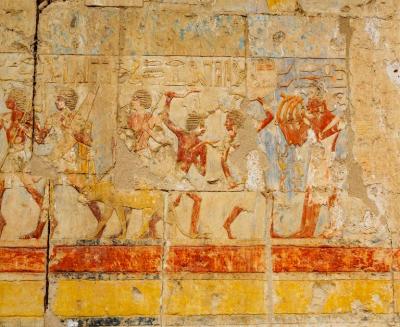

Osiris symbolizes hope for eternal life. He was considered the god and primary judge of the underworld. The ancient Egyptians honored him as a dead king, a former ruler who was brought back from the dead after being murdered by his brother Seth, the god of war, chaos, and storms.

The gods of the dead will then perform the weighing of the heat ceremony to assess if the person lived a virtuous and just life on earth. This ceremony was administered by Anubis, the jackal-headed god of mummification and the afterlife. He is one of the oldest and most revered gods of ancient Egypt. The judgment was recorded by Thoth, the god of writing, magic, and wisdom.

The confessions of the deceased would be listened to by a total of forty-two different gods known as the divine judges. The book of the Dead provided them with proper words to say to each one of the judges. This would help the person pass even if they were not completely innocent.

After the confessions, the heart would be weighed on a scale. On the other side of the scale would be a feather that embodied Maat, the goddess of harmony, justice, and truth. If the heart weighed the same as the feather, this means the person lived a just life and respected the divine and human social order on earth. Then they would achieve immortality and pass on to the afterlife eternally.

If their balance was not equal, the person would be considered guilty and his heart devoured by the demoness Ammit. Her body was part lion, hippopotamus, and crocodile—a truly terrifying and grotesque entity. This meant that the person would not survive in the afterlife and his life would end in shame and torment. There was a spell from the Book of the Dead, inscribed on their hear scarab amulet they could recite during the weighing to prevent their heart from betraying them.

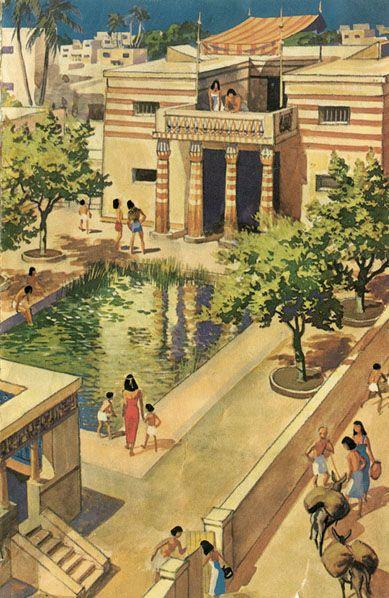

After passing all these challenges and tests, one would finally make it to the blessed afterworld. The soul would cross over the waters to the Field of Reeds. Here they would find family members and loved ones that had already passed before as well as other cherished animals they had lost. This paradise was where one could enjoy an eternal life full of one’s loved ones and cherished possessions, all of this with the immediate presence of the holy gods.

This realm was a reflection of the real world with blue skies, rivers, and boats, gods and goddesses to worship, and fields and crops. They would be granted a piece of land in the afterlife and were expected to maintain it eternally. This paradise had strong agricultural connections. However, if the person did not want to continue sowing and reaping eternally, the Book of the Dead offered a helpful solution. You could be buried with a small shabti doll to do the fieldwork instead. These shabti dolls were tiny funerary figures made of wood or stone and were often placed in the tombs with the dead. One could use these shabtis in the afterlife to do one’s agricultural work and the soul could go on relaxing by a river or walking their favorite dog.

The afterlife was seen as the perfect paradise because the soul is reunited with everything they lost in the moral world. The ancient Egyptians had one of the most comforting and relaxing afterlives ever imagined.

Comments